Layering stories at City School

I had been working in the ‘intervention classes’ for several months when an opportunity arose to hold three sessions in three successive weeks with the Year 8 (12-13-year-old) class. This class showed a huge relish for substantial myths and legends, and their teacher (SD) was keen to develop their skills as storytellers. I decided to tell the Blackfoot ‘Legend of Poia’ and to help them discover the ‘hero’s journey’ narrative structure underneath it by comparing it with the modern true story of William Kamkwamba, as a basis for creating their own mythic story. I had used this pairing of stories in a similar way once before, with a very different group of older teenagers at The Kitchen School; the younger group’s response to it was very different, but equally powerful and surprising. Indeed, in its intensity it led me to weigh up the responsibilities of a storyteller more seriously, and to value the 'alienating' effect of critical, dynamic engagement with story.

See 'City School' for an overview of my practice in this setting.

See 'City School' for an overview of my practice in this setting.

The structure of storyThroughout my practice I have grappled with the tension between ‘magic’ and ‘dynamic’ forms of storytelling: when to draw upon the absorbing enchantment of story and when to support young people to knock it down, pull it apart and get into the driving seat themselves. For one of the most significant thinkers on storytelling in education, Jack Zipes, it is vital that storytellers help young people become ‘familiar enough with the plot and structure of the original story to feel that they can play with it and alter it with their own ideas’ (1995:32). By telling different versions of the same story, he lays bare both the ideological baggage each version contains, and the narrative shape they have in common, thus preparing the ground to hand over the ‘means of representation’ to his listeners.

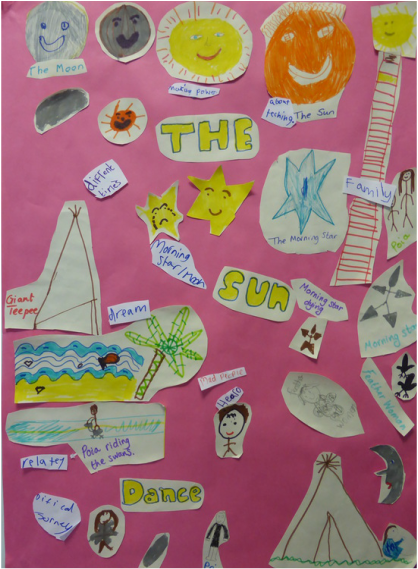

In a blog post I discussed my discomfort with establishing such critical distance between young people and stories; while I could see the value of doing so, I was concerned that this would be an engagement of story limited to the cognitive, depriving of them of the ‘wholeness’ of a story. Yet based on my growing familiarity with this group, I felt they would enjoy uncovering the devices of storytelling, and that this might boost their confidence in their own creative powers, oracy and literacy. I thus chose two stories – one mythic, one true – which conformed to Joseph Campbell’s ‘monomyth’ structure of the ‘Hero’s Journey’. The storiesThe ‘Poia’ cycle of stories concerns a Blackfoot Indian boy, child of a young human girl called Feather Woman and the Morning Star himself, who has to travel back to his grandparents’ Sky Country to overcome the scar laid on him for his mother’s defiance, and to bring back the ‘Sun Dance’ which will help his people grow and develop. My main source for the story is Walter McClintock’s (1910) The Old North Trail; or, Life, Legends and Religion of the Blackfeet Indians; for a synopsis of it see here.

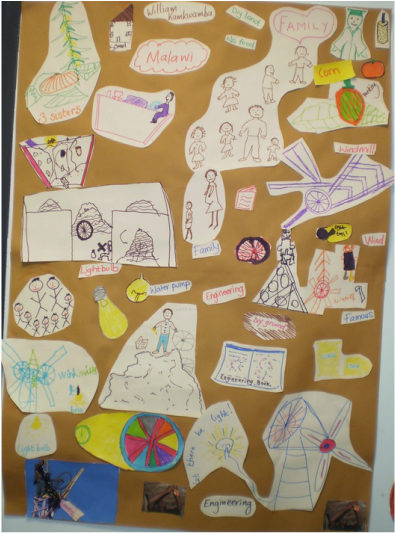

William Kamkwamba is a young Malawian man who, excluded from school by poverty and famine, managed to develop simple wind turbines out of waste materials and bring electricity to his village, despite the suspicion and opposition of his family and village elders. He has documented his experiences in a book, The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind, given TED talks, and become an engineer and social entrepreneur. Perhaps unsurprisingly, his inspiring story can be read as a classic ‘hero’s journey’. A synopsis is available here. Running with the resonancesI told the stories as ‘sparsely’ as I could; finding as ever, as Walter Benjamin (1973(55)) said, that the more a storyteller can resist superfluous detail and psychological interpretation, the easier it is for the listeners to join it to their own experience, and find a space for it in their own mental landscape. This group had an already established pattern of ‘retelling’ stories through making posters, each person choosing their own strongest image of the story to draw, and adding key words. These posters were a form of what Matthew Reason and I call ‘creative copying’, ‘a detailed and close revisiting’ that was ‘never purely derivative’ (2016:7-8); choices were made and emphases were shifted. They remained on the wall for months, at the pupils’ request. The posters show that the chords these stories struck were quite different than for the Kitchen School group. In ‘Poia’, it was the elemental power of the sun and moon over Poia’s fate, and the power he felt coursing through him; in ‘William Kamkwamba’, it was his large, needy family, his boredom and his exclusion to the ‘rubbish tip’ of life.

Common to both groups, however, was the feeling of ‘outsiderliness’ evoked by the stories. This need not have been the case; both heroes have moments of being surrounded and celebrated by their communities. Yet faced with the almost too-deep quality of the class’ listening, I felt the figures of Poia and William emerging as necessarily lonely, irresolvably misunderstood. Mr Imagination: the class' hero |

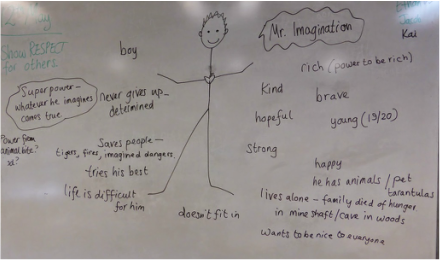

The Legend of PoiaWilliam Kamkwamba's StoryStructure uncoveredOverlaying one story onto the other, the group were delighted to discover the similarities between them and to establish their own version of the ‘hero’s journey’ structure within which both were composed. We drew a ‘stick man’ on the board and created our own ‘hero’, and then, using a ‘chain story’ format, developed his ‘journey’. I was taken aback by the fluency of this exercise, which drew in even the most reluctant pupils. Their story seemed to take shape by pre-agreed consensus.

I recorded the story verbatim, then edited it slightly to make it flow in writing, so as to perform it back to them the following week, and give them copies of it (see full text below). This ‘returning’ of a story to a group who have authored it is often a tense moment; they often do not recognise it, or feel it has been twisted, even if no word has been altered. Yet it can also dignify a story, and in this context it felt like we were adding it to a canon of important stories. They christened their hero ‘Mr Imagination’ - read his story here: |

| mr_imagination’_–_part_1.pptx | |

| File Size: | 104 kb |

| File Type: | pptx |

Guiding or being led?

On re-reading ‘Mr Imagination’, I was concerned as to the undercurrents both of the story and of the whole project. I wrote in my blog: ‘Creating a marginalised character to represent a marginalised group of young people might be a horizon-limiting thing - strengthen the bonds between them but make them feel more cut-off from others.’ Was this a ‘closed story’, as Nick Rowe (2007) discusses in relation to playback theatre, one that tightened rather than loosened the knots defining what seemed to be their strongly shared self-image? Could the intensity of the young people’s engagement be a negative as well as a positive thing; had it led me to follow them to the ‘wrong’ place? I felt a tension between the value of meeting young people in dialogue through story – letting it take shape in the space between me and them - and my responsibility to guide them through it.

In any event, my concern that analysing the stories’ structure would make their power dwindle away to nothing certainly seemed misplaced. Far from restricting their impact to the cognitive sphere, at least in this group, exposing the structure seemed almost to strengthen the irresistible momentum of the solitary 'hero's journey'.

Indeed, I had to look again at the fruits of Jack Zipes’ long experience in schools. Zipes deals with ‘unacceptable’ messages or stereotypes in fairytales not by sanitising or avoiding them, but by following them up with subversive versions of the same story. Over the coming months, I deliberately sought out contrasting, countervailing and provocative stories for this group, which might challenge somewhat the hold of ‘Mr Imagination’.

In any event, my concern that analysing the stories’ structure would make their power dwindle away to nothing certainly seemed misplaced. Far from restricting their impact to the cognitive sphere, at least in this group, exposing the structure seemed almost to strengthen the irresistible momentum of the solitary 'hero's journey'.

Indeed, I had to look again at the fruits of Jack Zipes’ long experience in schools. Zipes deals with ‘unacceptable’ messages or stereotypes in fairytales not by sanitising or avoiding them, but by following them up with subversive versions of the same story. Over the coming months, I deliberately sought out contrasting, countervailing and provocative stories for this group, which might challenge somewhat the hold of ‘Mr Imagination’.

The property of the class

A year later, SD and I held a reflective focus group in which we laid out everything the pupils had made in response to stories I had told them. Of all the many stories we had discussed and transformed together, the Year 9 group unanimously and forcefully chose ‘Mr Imagination’ and its parent stories as the most memorable. One boy, a particularly skilled storyteller, retold it in considerable detail to the other classes present. It was an important reference point for all the Year 9 pupils present in articulating what they felt to be particular or valuable about storytelling, as the following digest of the focus group indicates.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Several things interested me about the group’s emphatic pride in the story. Firstly, this was the project least connected to their curriculum, and yet it was the one from which they were sure they had learnt or gained most – confirming the similar finding of Patrick Ryan and Donna Schatt (2014), who interviewed adults who had had stories told to them as children. Secondly, that there need not be a tension between the moments of dynamic ‘laying bare’ and magical ‘suspending disbelief’; that a dialogic relationship between these two impulses is possible and young people can create something in the space between them, in which they can invest great belief and value. It was work like this, indeed, that helped me recognise a ‘dialogic chronotope of storytelling’ which puts both modes of storytelling at young people’s service. And thirdly, that there was no way for me to determine whether Mr Imagination was a ‘helpful’ or a ‘harmful’ story; it was simply part of the property of the class now, to be integrated by them as they choose into all the other stories they would tell and hear, read and write in their lives.

Several things interested me about the group’s emphatic pride in the story. Firstly, this was the project least connected to their curriculum, and yet it was the one from which they were sure they had learnt or gained most – confirming the similar finding of Patrick Ryan and Donna Schatt (2014), who interviewed adults who had had stories told to them as children. Secondly, that there need not be a tension between the moments of dynamic ‘laying bare’ and magical ‘suspending disbelief’; that a dialogic relationship between these two impulses is possible and young people can create something in the space between them, in which they can invest great belief and value. It was work like this, indeed, that helped me recognise a ‘dialogic chronotope of storytelling’ which puts both modes of storytelling at young people’s service. And thirdly, that there was no way for me to determine whether Mr Imagination was a ‘helpful’ or a ‘harmful’ story; it was simply part of the property of the class now, to be integrated by them as they choose into all the other stories they would tell and hear, read and write in their lives.

References

- Benjamin, W. 1973. "The Storyteller: Reflections on the Works of Nikolai Leskov." In Illuminations, edited by H. Arendt, 83-109. London: Fontana.

- Reason, M. and Heinemeyer, C. 2016. "Storytelling, story-retelling, storyknowing: towards a participatory practice of storytelling." Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance 21(4): 558-573.

- Rowe, N. 2007. Playing the Other: Dramatizing personal narratives in playback theatre. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Ryan, P. and Schatt, D. 2014. "Can You Describe the Experience?" Storytelling, Self, Society 10 (2):131-155.

- Zipes, J. 1995. Creative Storytelling: Building community, changing lives. London: Routledge.