No space for stories at City School

A feedback exercise, after my pilot project with all the Year 8 classes at City School, indicated that teachers were broadly in agreement that “the pupils need a creative spark, we’ve been very methodical this year”. While they observed that pupils' "creative writing is wildly unrealistic” and benefited from the inspiration of storytelling, there was some consensus that giving class time to storytelling didn’t “support skills”, nor did it “seem especially useful in terms of being focused on assessments, etc.” The teachers were flat out trying to help the pupils achieve the exam success they needed, and also discussed in the staffroom how they had very little time or opportunity to respond to pupils’ interests.

It seemed clear that there was limited further scope for storytelling in lesson time, but their comments confirmed my own sense that there would be a great value in establishing an informal storytelling space for pupils. Current lunchtime activities were restricted to a games room for ‘vulnerable’ pupils to escape the hurly-burly (and sometimes the bullying) of the playground. I felt a storytelling club could open up what Nicolas Bourriaud (1998) calls an 'interstice', a space within which different kinds of communication could occur – among pupils, between me and the pupils, and between pupils and teachers (as the English department agreed to support the initiative).

Perhaps from this basis, outside the confines of the curriculum and in a space 'bracketed' from the social tensions between groups, interested pupils could exercise their own small influence on the texture of school life. I did not know what they might want to do with stories. Yet I was ready to facilitate whatever it might be; reading Felix Guattari's Chaosmosis (1995), I recognised his desire to 're-singularise' institutions like schools through the arts: 'How do you make a class operate like a work of art? What are the possible paths to its singularisation, the source of a “purchase on existence” for the children who compose it?' (132-3)

The group started running one lunchtime a week at the beginning of the autumn term of 2014. However establishing it was a fraught process. Many pupils came along, but for diverse reasons.

The following analysis is interspersed with extracts from my field notes. See 'City School' for an overview of my practice in this setting.

It seemed clear that there was limited further scope for storytelling in lesson time, but their comments confirmed my own sense that there would be a great value in establishing an informal storytelling space for pupils. Current lunchtime activities were restricted to a games room for ‘vulnerable’ pupils to escape the hurly-burly (and sometimes the bullying) of the playground. I felt a storytelling club could open up what Nicolas Bourriaud (1998) calls an 'interstice', a space within which different kinds of communication could occur – among pupils, between me and the pupils, and between pupils and teachers (as the English department agreed to support the initiative).

Perhaps from this basis, outside the confines of the curriculum and in a space 'bracketed' from the social tensions between groups, interested pupils could exercise their own small influence on the texture of school life. I did not know what they might want to do with stories. Yet I was ready to facilitate whatever it might be; reading Felix Guattari's Chaosmosis (1995), I recognised his desire to 're-singularise' institutions like schools through the arts: 'How do you make a class operate like a work of art? What are the possible paths to its singularisation, the source of a “purchase on existence” for the children who compose it?' (132-3)

The group started running one lunchtime a week at the beginning of the autumn term of 2014. However establishing it was a fraught process. Many pupils came along, but for diverse reasons.

The following analysis is interspersed with extracts from my field notes. See 'City School' for an overview of my practice in this setting.

Two Tribes

Early on, it became evident that there were two main sets of young people who were attracted to ‘Liars’ Lunch’: a group (or rather, a number of individuals from different year groups) of earnest and sensitive young people interested in literature, folktale and myth, and a large cluster of restless, ‘naughty’ girls who roamed the school looking for an interesting place to be. There were also a small number of other young people who fitted into neither of these, but it was these two that set the tone. Both ‘tribes’ were sparky and full of ideas, and perhaps both, in different ways, were awkward fits in the school environment. Neither needed any convincing that this was ‘their’ space to shape how they wanted it.

The problem lay in the diametrically opposed ways they wanted to interact with story. The former group, the ‘old guard’ as I called them secretly, loved the language of fairytale and the ‘magic’ of stories – though they rarely listened quietly, preferring to take over the telling, suggest changes, tell or read out their own stories. Sessions dominated by them led (on their initiative) to retellings of stories in the form of drama or creative writing – like this:

The problem lay in the diametrically opposed ways they wanted to interact with story. The former group, the ‘old guard’ as I called them secretly, loved the language of fairytale and the ‘magic’ of stories – though they rarely listened quietly, preferring to take over the telling, suggest changes, tell or read out their own stories. Sessions dominated by them led (on their initiative) to retellings of stories in the form of drama or creative writing – like this:

The ‘naughty-but-needy’ group, in contrast, had no interest in my stories at all. They wanted to make stories out of nothing, play games, mixing the fantastical, the subversive and the downright rude into crazy concoctions. When they got their way there was no room at all for magic.

|

November: OH DEAR – very different ways of having fun. The ‘old guard’ want to do great things: create a walkabout storytelling performance round school, make a film. The ‘naughty-but-needy’ girls launch into the middle of this (usually late) with a crash. They do genuinely want to hear and tell stories, play games, but keep breaking down into teasing, uproar. When they had gone I tried to assure the ‘old guard’ that we would make it work for everyone. We decided on some wording for the school newsletter like ‘All serious storytellers and storylisteners welcome’.

December: Ms S (teacher) said N told her she is only going ‘for the free biscuits’ and had nearly banned her for this – but in fact N was attentive, visibly struggling with her own need to be listened to, desire to seek attention, wildness of limbs... It might be this very diversity that makes Ms S nervous – the potential for bullying of the vulnerable kids, volatility and meanness… I hope there is potential for the group to soften some of these social barriers, give individuals a role and recognition. But maybe this is pie-in-the-sky. |

Finding our feet

By the end of the first term, a tentative mutual respect had begun to build – not a ‘safe space’, but a modus vivendi. We started to find some common ground on which to build a shared vernacular: games and activities which encompassed both the subversive and the earnest drives in the group. Our common currency was, in fact, interruption. Both groups of young people loved the interrupted story – the insertions of their ideas into mine or into each other’s. I played with this in the games I proposed, and often the young people led the way.

On one occasion an ‘old guard’ girl brought along a ghost story she had written and declared her intention to read it to the whole group. The others found it so chilling that we started interjecting our own comedic asides to lighten it. Halfway through, the ‘naughty-but-needy’ group crashed into the space. I told them what was going on and that they could prepare themselves to be alarmed. The reader started again and the newcomers were initially stunned into silence by her command of the room. However they quickly got the hang of the game and a noisy peace descended.

In moments like these, groups whose social roles were normally antagonistic were sharing space, to the English teachers' surprise. We were inhabiting an interstice, described by Bourriaud as ‘a space in social relations which…suggests possibilities for exchanges other than those that prevail within the system…’ (1998:44).

On one occasion an ‘old guard’ girl brought along a ghost story she had written and declared her intention to read it to the whole group. The others found it so chilling that we started interjecting our own comedic asides to lighten it. Halfway through, the ‘naughty-but-needy’ group crashed into the space. I told them what was going on and that they could prepare themselves to be alarmed. The reader started again and the newcomers were initially stunned into silence by her command of the room. However they quickly got the hang of the game and a noisy peace descended.

In moments like these, groups whose social roles were normally antagonistic were sharing space, to the English teachers' surprise. We were inhabiting an interstice, described by Bourriaud as ‘a space in social relations which…suggests possibilities for exchanges other than those that prevail within the system…’ (1998:44).

|

December: It has taken 12 weeks but we are getting well-established. Some of the ‘new wave’ girls came in, and when challenged by Miss S said they ‘always come’. When A struggled to speak, there was a visible tussle between the forces of kindness and the forces of mockery – and kindness won – and she managed to say something. In fact almost all of them did. Nobody turned the story round to ‘willies’; E did sound effects and, even when the teacher was not in the room, this did not get out of control.

|

The interstice squeezed

Such moments were, however, the exception and not the rule. I felt that, if we could contain the tensions between the young people, an exciting cross-fertilisation of ideas between them would result, and that this was achievable given time and lateral thinking. Yet the school's lunch breaks were kept very short to limit the potential for disruptive behaviour, and often further shortened by detentions. Too often, a promising start with the faithful 'old guard' would be thwarted by noisy and subversive late arrivals, or the former would sulkily refuse to enter if the latter were already present.

|

January: It is getting very difficult to handle these two different constituencies!... I don’t want to make it a group for the vulnerable kids alone, rather I want to use storytelling to bring these disparate groups together to really listen to and respect each other... Can it though? If one group is passing the door and checking whether the other has arrived before they decide whether to come in? The best sessions have been those where everyone has turned up early, where a teacher has been present or looked in sometimes. Where the kids have built on my introductory activity by suggesting something constructive themselves, like asking someone (usually W) to tell one of her stories….I have to remember that the pupils have very limited experience of self-organising or doing open-ended tasks together… I don’t want to impose discipline – at least, no more than providing activities and allowing them to go off on tangents if they are constructive.

To give the group a holding structure I need the full half hour and everyone needs to be there by 1:10, sign in, sit down. Then we need to close the doors, play a quick warm-up game and get into the main activity the group has agreed on. This is the appropriate ‘entrance bar’ to set. This will make the young people choose whether they really want to be there. I fear we will lose the ‘naughty-but-needy’ girls though… |

In the New Year I made an attempt to establish a pattern of arriving on time and committing to the session:

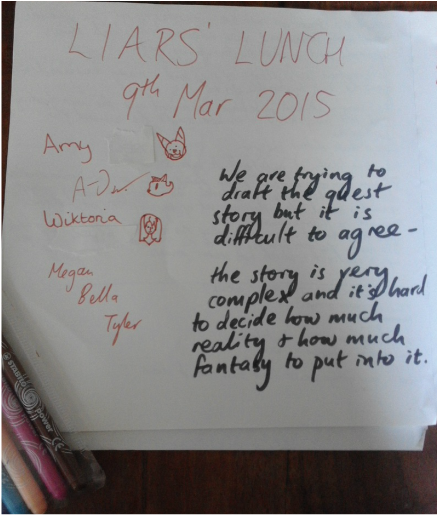

However, this did not result in any marked improvement in timeliness, which was essentially beyond the pupils' control. Moreover, each project the group conceived was frustrated by the lack of time, or the school's inability to facilitate it (as the teachers were too busy and the curriculum was too tight). Thus, for example, although the pupils worked for some time towards a performance for feeder primary school children visiting City School, staff did not get around to making the arrangements necessary for them to occupy some space on the visit programme, or have some additional rehearsal time. Afternoon and weekend sessions were dismissed as impossible because of the keenest members' caring and homework responsibilities.

I came to see the lack of time as something more than an inconvenience. It was a 'choice' imposed on the school by the demands of the curriculum and the pressure to suppress rather than respond to the challenging behaviour of their pupils, which straitjacketed both pupils' and teachers' time, and limited their potential to develop their own interests and initiative. While the teachers did see the need to actively nourish the social environment, this goal was simply incommensurate with their key drivers as a mainstream secondary school.

It is a source of disappointment to me that all my successes in establishing long-term storytelling with young people have been in non-mainstream, 'protected' or 'special' settings, where staff are at liberty to use their own discernment and put the young people's interests first.

It is a source of disappointment to me that all my successes in establishing long-term storytelling with young people have been in non-mainstream, 'protected' or 'special' settings, where staff are at liberty to use their own discernment and put the young people's interests first.

References

- Bourriaud, N. 1998. Relational Aesthetics. Les presses du reel.

- Guattari, F. 1995. Chaosmosis: an ethico-aesthetic paradigm. Trans. P. Bains and J. Pefanis. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.